ASYNCHRONOUS PROGRAMMING IN PYTHON

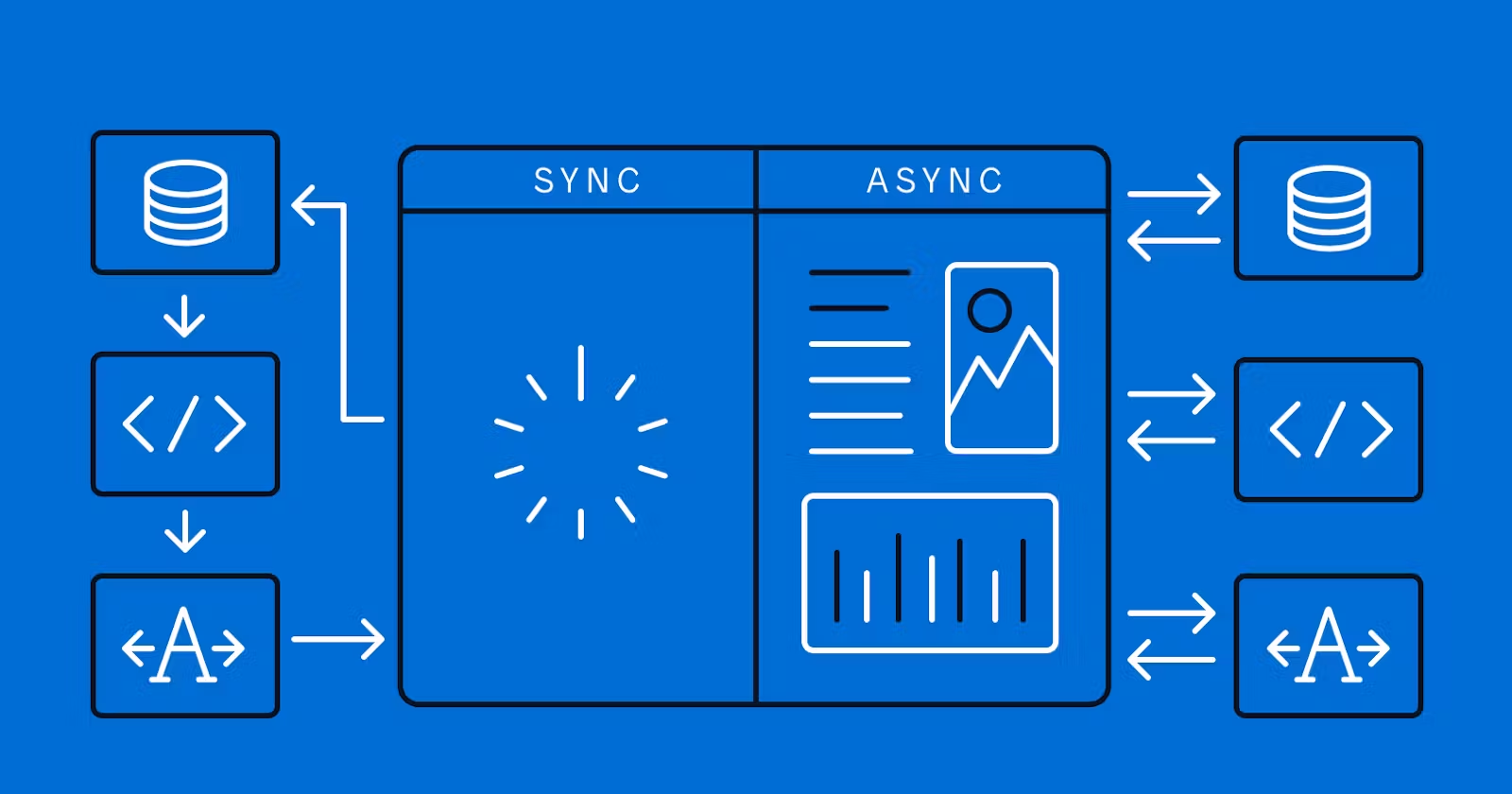

Sync vs Async

What is a synchronous programming?

Synchronous programming is a programming paradigm in which operations are executed sequentially, one after the other. In this model, each operation waits for the previous one to complete before moving on to the next step. This sequential execution can lead to ‘blocking’ operations, where certain tasks may take a significant amount of time to finish. These blocking operations can pause the entire program’s execution, forcing it to wait until the time-consuming task is done before it can proceed. Let’s understand it with an example:

from time import sleep

def foo():

print("in foo")

sleep(10) #mimicing some blocking operation

print("end foo")

foo()

print("Termination of the program")

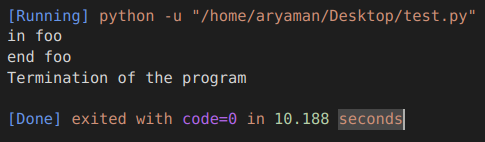

Here, you can observe that the program’s execution was strictly sequential, and this led to a halt in the entire program due to a blocking operation inside the foo() function, which took 10 seconds to complete. After this 10-second delay, the program continued its execution.

This situation isn’t ideal because these blocking operations could encompass a wide range of tasks, such as database queries or waiting for API responses, and they unnecessarily delay the execution of unrelated parts of the program. This is precisely where the concept of asynchronization becomes valuable.

So, what is asynchronization?

In computer programming, asynchrony encompasses events that occur independently of the primary program flow and methods for managing these events. In essence, asynchronization implies that you can proceed with executing other sections of code without the need to wait for a particular task to finish.

The first thing when creating an asynchronous program creating a coroutine.

What’s a coroutine in Python?

A coroutine is simply a wrapped version of a function that allows it to run asynchronously. I would recommend using Python 3.7+ to follow the following guide.

import asyncio #importing async library

async def main(): #defining a coroutine object

print("hello world")

print(main()) #Output - <coroutine object main at 0x7f013de5fd80>

To create a coroutine object you just need to create a function normally and add an async keyword in front of it. What it essentially does is create a wrapper around this function.

So when we call this function it creates a coroutine object <coroutine object main at 0x7f013de5fd80> This coroutine object works just like a function and can be executed. To execute a coroutine you need to await it.

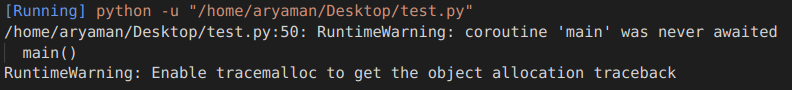

Wait, WHAT?! What’s awaiting? Let me show you the output of the above snippet of code.

As we have a coroutine object now, it does not work like a regular Python function.

Async Event-Loop

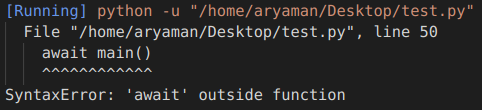

Ok. No worries. Let me just await the main() function call and then it should work, right?

import asyncio

async def main():

print("hello world")

await main()

Oh, no! It gave an error. So what’s the issue? The reason it’s not running our code because we haven’t created an event-loop.

Whenever we create an asynchronous program in Python we need to start/create an event loop. An event loop typically refers to the core mechanism used for managing and handling asynchronous or non-blocking operations. It’s a fundamental component of many asynchronous programming frameworks, such as asyncio which we are using in our study. It is responsible for this simple async syntax, we are seeing here, in the backend. We must start an event loop in whatever thread we are running this asynchronous program in.

import asyncio

async def main():

print("hello world")

asyncio.run(main())

Hence, to start an event loop we use asyncio.run() and pass it a coroutine object which acts as an entry point to the event loop.

Await keyword

import asyncio

async def main():

print("awaiting foo...")

await foo("inside foo")

print("finished awaiting foo")

async def foo(text):

print(text)

await asyncio.sleep(1)

asyncio.run(main())

If we look inside the foo() function, the await keyword is required to run an object of coroutine, because if you just write something like asyncio.sleep(1) you are just creating a coroutine but not executing it.

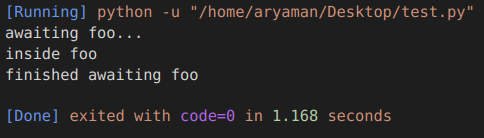

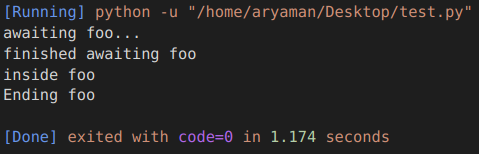

And we are allowed to use await because we are present inside an asynchronous function. So, if we try to see the output of the entire code, it would be as follows:

We can see that we awaited the foo() function call, and going inside the foo() function we waited for 1 sec and then the execution was back to the main() function.

But this is not entirely useful, as we can see that this seems to be just another way of writing a synchronous program as we are waiting for

foo()to execute and then we go forward with the execution in themain()function.The whole point of asynchronization is to run something else while we are waiting for some other part of the execution to finish which is not achieved here. This can be achieved by creating a task.

asyncio Tasks

import asyncio

async def main():

print("awaiting foo...")

task = asyncio.create_task(foo("inside foo"))

print("finished awaiting foo")

async def foo(text):

print(text)

await asyncio.sleep(1)

print("Ending foo")

asyncio.run(main())

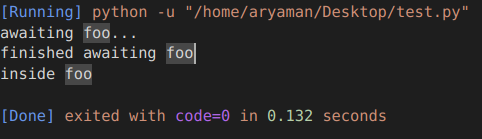

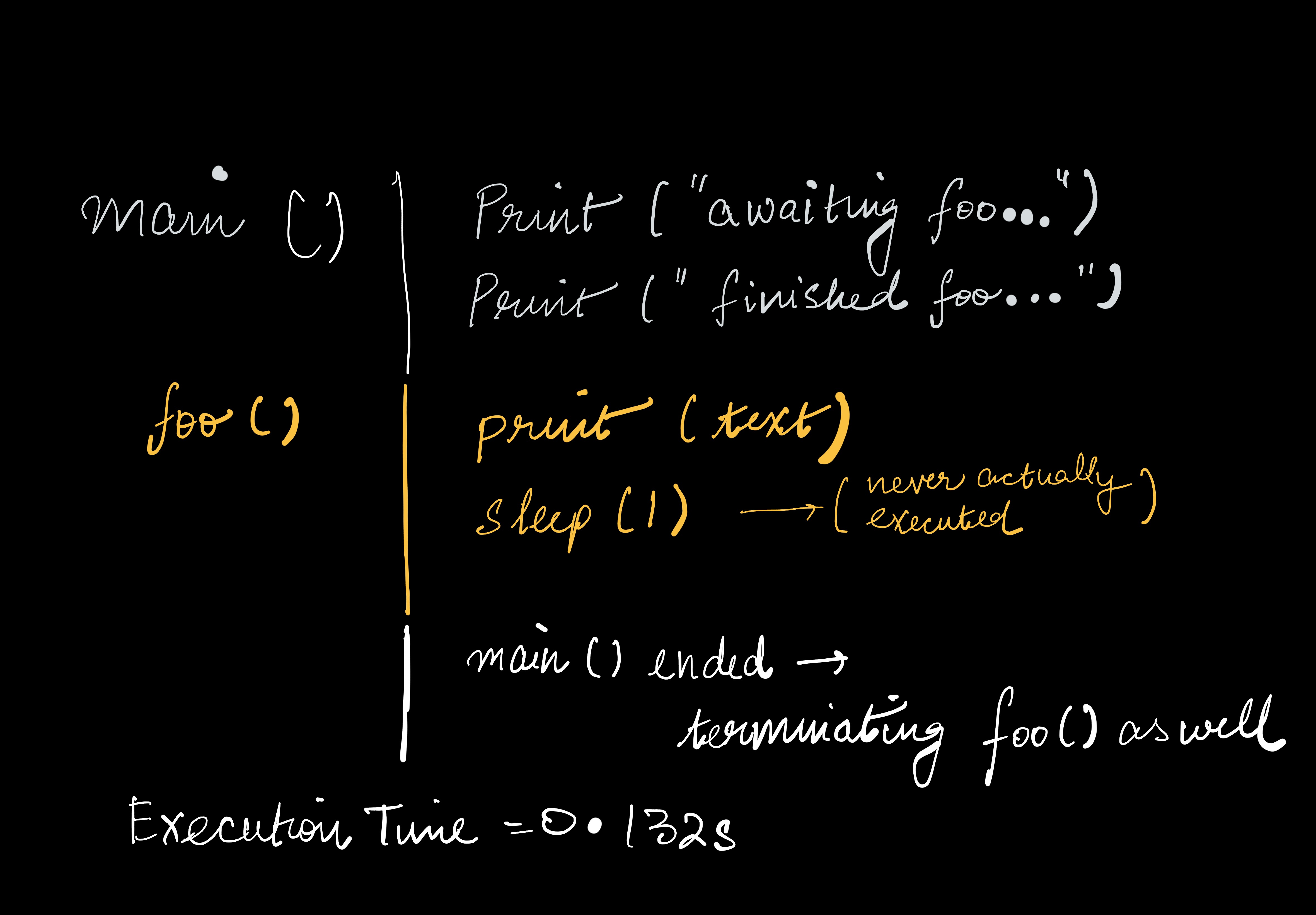

If we see the code above, we are creating a task using create_task() function and passing a coroutine object to it. This essentially tells the program to run the task as soon as there is some kind of waiting in the main line of execution.

Analyzing the output, we can see that the execution of the main() function is completed and then the execution of foo() starts.

VERY IMPORTANT RESULT

You can also see that the “Ending foo” never printed and the execution time of the program was only 0.132 sec. Weren’t we sleeping for 1 sec, so shouldn’t the execution time be at least 1 sec and “Ending foo” should be printed after? What happened here is when the

foo()function started sleeping for 1 sec, the execution of the program was given back to themain()function, and as there weren’t any tasks left in themain()function, it terminated and as a result terminated the execution offoo()as well which never completed its execution.

So if I want to wait for the foo() to finish it’s execution before main() terminates I will need to await it, essentially preventing the main() function to terminate prior to the completion of the task foo().

import asyncio

async def main():

print("awaiting foo...")

task = asyncio.create_task(foo("inside foo"))

print("finished awaiting foo")

await task

async def foo(text):

print(text)

await asyncio.sleep(1)

print("Ending foo")

asyncio.run(main())

Hence the output would be as follows (note the time taken for execution).

More Examples

import asyncio

async def fetch_data():

print('Start fetching')

await asyncio.sleep(2) #mimcing fetching data via some request

print('Done fetching')

return {'data': 1}

async def print_numbers():

for i in range(10):

print(i)

await asyncio.sleep(0.25) #mimcing waiting for a response

async def main():

task1 = asyncio.create_task(fetch_data())

task2 = asyncio.create_task(print_numbers())

# need to get the {'data': 1} value from fetch_data

print(task1)

asyncio.run(main())

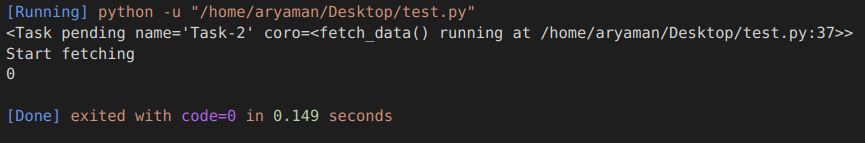

Imagine the above scenario where I need to get the return value {'data': 1} from the fetch_data() coroutine executing via task1 in the main() function. Hence, I declare the task1 and print(task1). It would have worked in a synchronous environment. But, from what we have learned so far this is counterintuitive.

As we can see in the output of the above code, we never awaited for the task to be completed, hence we would never get the return value from the function (can relate to promises in JavaScript).

Hence the correct code should be as follows:

import asyncio

async def fetch_data():

print('Start fetching')

await asyncio.sleep(2) #mimcing fetching data via some request

print('Done fetching')

return {'data': 1}

async def print_numbers():

for i in range(10):

print(i)

await asyncio.sleep(0.25) #mimcing waiting for a response

async def main():

task1 = asyncio.create_task(fetch_data())

task2 = asyncio.create_task(print_numbers())

# awaiting for task1 to be completed and then using

# the value it returned

value = await task1

print(value)

await task2

asyncio.run(main())

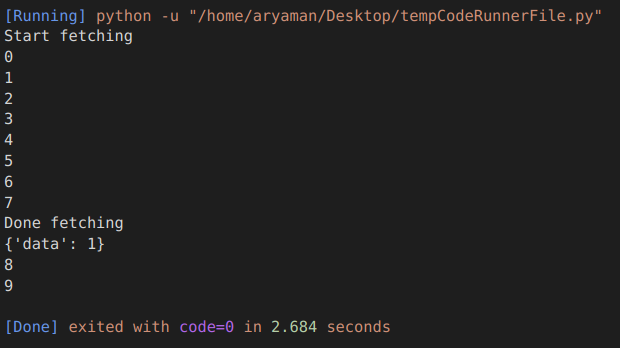

As we can see in the output, because we awaited for task1 to finish, we can get the value returned by it and print it later. We can further see that as fetch_data() was waiting for 2 sec, for loop in print_numbers() executed 8 times (~2 sec) and gave a chance back to fetch_data() as it’s waiting time had ended.

Conclusion

When we write async def func_name(), what we are doing is wrapping another function with an asynchronous version of it. That version is the Coroutine. To run the coroutine you must await it in some way or add it to the event loop. You can add it to the event loop by creating a task ( asyncio.create_task(func_name()) ). This allows you to start multiple coroutines concurrently. Finally, to start your asynchronous program you must create an event loop which can be done by asyncio. run(driver_func()) and passing an entry point coroutine which is generally the driver function of your program (for example the main function).

One thing to note is that at a time only a single execution is happening, and it is not to be confused with parallel processing or threading.