BREAKING BOUNDARIES

Python faces challenges in fully exploiting the growing capabilities of modern hardware. As hardware continues to advance with more CPU cores, faster processors, and abundant memory, Python’s inherent design and execution model can often fall short in taking full advantage of these resources. Its single-threaded nature and certain architectural choices can result in suboptimal performance in scenarios where parallelism and hardware acceleration are vital. This limitation prompts developers to seek alternative solutions, such as integrating Python with external libraries, languages, or technologies, to overcome these hardware-related constraints.

NEED OF SIMULTANEOUS EXECUTION IN PYTHON

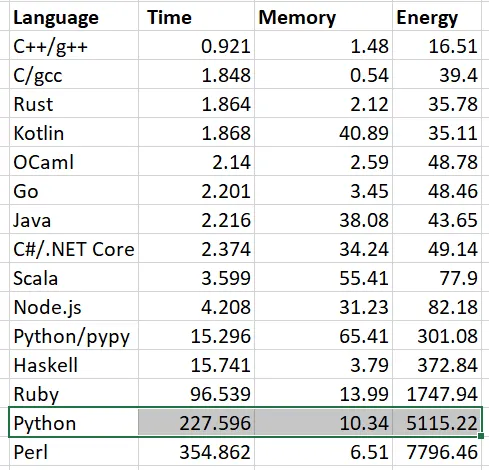

We all know that the main advantage of using python is that it is easy to learn, easy to use, and highly versatile, supporting developer productivity. However, Python is also notoriously slow. Programs written in languages such as C++, Node. js, and Go can execute as much as 30-40 times faster than equivalent Python programs.

Even though Python is constantly being optimized to work faster, we simply can’t rely on the basic single-threaded execution codes as they are too slow. Hence the need for simultaneous execution.

SIMULTANEOUS EXECUTION POSSIBILITIES IN PYTHON

3 big contenders for dealing with multiple tasks in Python -

-

Asyncio - In computer programming, asynchrony encompasses events that occur independently of the primary program flow and methods for managing these events. In essence, asynchronization implies that you can proceed with executing other sections of code without the need to wait for a particular task to finish.

For example, asynchronous programming is beneficial to use where multiple database interactions are there, database read/write operations generally take a lot of time hence the flow of execution can be changed instead of the database call to get completed.

-

Cooperative pausing/waiting

-

Good for I/O bound processes

-

-

Threading -

-

Python runs on single thread on single CPU

-

GIL is a global lock around the entire Python interpreter. In order to advance the interpreter state and run the python code a thread must require the GIL. Hence, it is possible to have multiple python threads in the same process, only one of them can be executing the python code. While this happens, rest of them must wait to receive the GIL.

-

Non-cooperative pausing/interrupting

-

Good for I/O bound

-

Good to do long-running ops w/o blocking (example GUI application)

-

-

Multiprocessing -

-

Create different processes which have their own GIL

-

Better where all processes are completely independent of each other

-

Threading

Let’s take a for loop as an example, this loop is a CPU intensive task.

### Code 4.1: CPU Intensive task example

DO = 100000000

ans = 1

def foo(n):

global ans

for i in range(n):

ans += 2

foo(DO)

print(ans)

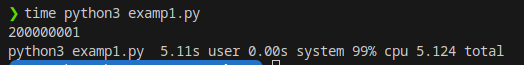

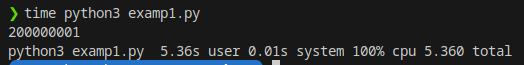

As this was a simple single threaded task, it took around 5 secs and was 99% CPU intensive.

Okay, so if I have 2 loops like this running on a single thread, it would take around 10s. This is very bad.

### Code 4.2: Extension of Code 4.1, 2 CPU Intensive tasks

DO = 100000000

ans = 1

def foo(n):

global ans

for i in range(n):

ans += 2

foo(DO)

foo(DO)

print(ans)

No issues, as these are CPU intensive tasks, we can run both the tasks on different threads. Hence, simultaneous execution would help us run 2 threads simultaneously and concurrently and the time would be reduced by half.

### Code 4.3: CPU Intensive tasks executed in different threads

from threading import Thread

DO = 100000000

ans = 1

def foo(n):

global ans

for i in range(n):

ans += 2

t1 = Thread(target=foo, args=(DO//2,))

t2 = Thread(target=foo, args=(DO//2,))

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()

print(ans)

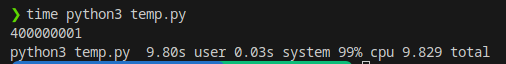

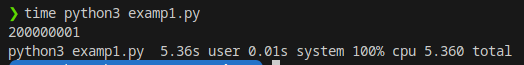

If this was true multithreading, the time taken for a for loop of half the range of the previous example should be half of the previous time taken, i.e. around 2.5 sec.

But we can see it again took roughly the same time. Why is this happening? To understand this we need to look into the core concept of Cpython - GIL.

GIL?! What is GIL?

Before discussing GIL, it is important to note that we are discussing this in terms of Cpython.

-

Python - definition of programming language we know, PEP - python enhancement proposals

-

Cpython - physical implementation of the ideas in “Python” in C language

Generally when we talk about python, we refer to the Cpython implementation of the language only.

Moving forward -

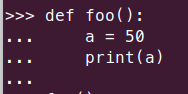

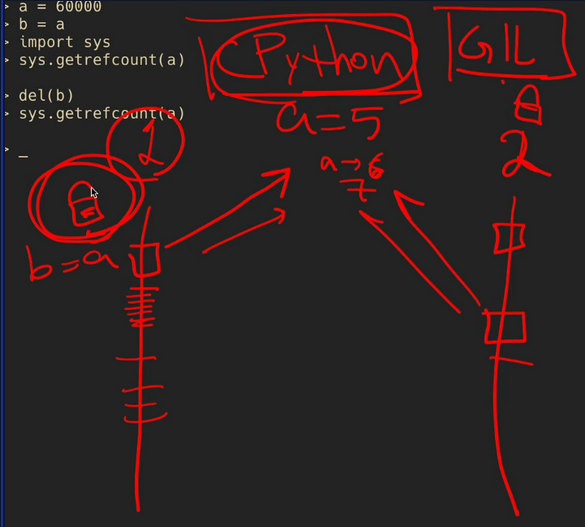

I created a function foo() where I allocated a = 50.

50 will be stored in memory and the variable a would be pointing to it. So the reference count of the memory where 50 is stored would be 1. But now, when the function is finished, the memory location has to be cleared/dereferenced. Hence, the reference count would be decreased by 1.

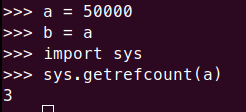

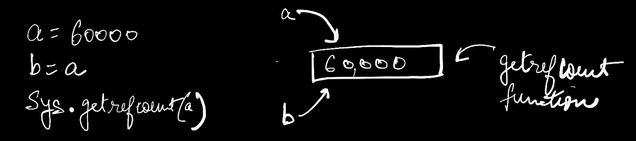

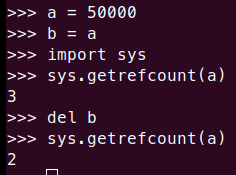

Reference counting in CPython - At a very basic level, a Python object’s reference count is incremented whenever the object is referenced, and it’s decremented when an object is dereferenced*.*

The memory deallocation is done in different ways in different languages but in python when the reference count of a memory location becomes 0, python knows that that memory location can be used for storing something else.

Example - Garbage collectors is used by java

Then, why do we get a reference count of ‘a’ as 3 here?

This is the reason.

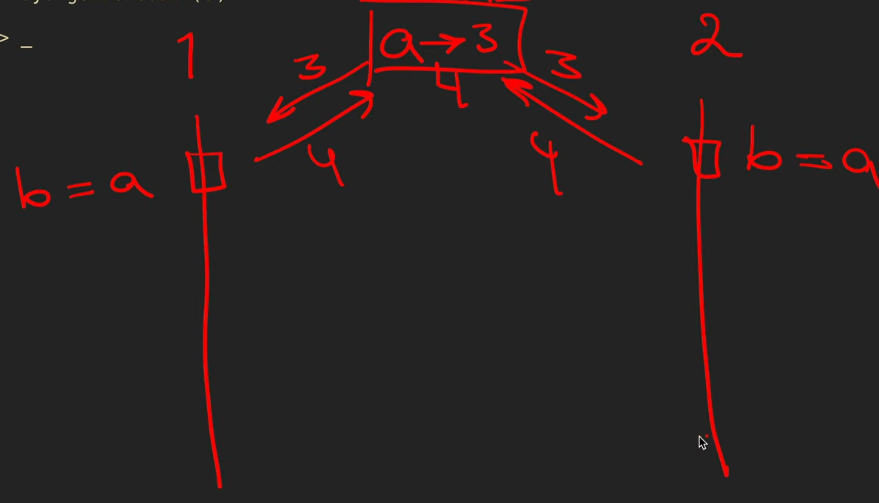

The main issue comes, when there is concurrency involved in python threads -

Imagine 2 threads are running simultaneously, in CPython. Reference Count of memory location pointed by variable ‘a’ is 3. Thread 1 and 2 ask what is the reference count of ‘a’ and both get 3. Now I do ‘b=a’ in thread 1 so the reference count increases to 4. At the same time I do ‘c=a’ in thread 2 and it also updates the reference count to 4.

But shouldn’t the reference count be 5? Race conditions occur in such cases. Hence, the requirement for concurrency management or GIL (Global Interpreter Lock) is required

In a real scenario if I have 4 threads running concurrently, thread 1 acquires the GIL, does some computation and waits for some I/O. In that time, the GIL is transferred to thread 2 which again does some task and starts waiting for something, for example a mouse click in the GUI. Again the GIL is transferred to a different thread. That’s why multithreading works in cpython.

But if I have 2 different threads and both want to work with the CPU, then GIL is not a good option.

Python 1.0 (1994): Python was initially designed without the GIL. In its early versions, Python used a simple reference counting mechanism for memory management. However, this approach had limitations, especially when dealing with circular references, which could lead to memory leaks.

Python 1.5 (1999): With Python 1.5, Guido van Rossum, the creator of Python, introduced the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) as a solution to the multi-threading problems.

Referring back to the example code 4.3-

### Code 4.3: CPU Intensive tasks executed in different threads

from threading import Thread

DO = 100000000

ans = 1

def foo(n):

global ans

for i in range(n):

ans += 2

t1 = Thread(target=foo, args=(DO//2,))

t2 = Thread(target=foo, args=(DO//2,))

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()

print(ans)

If this was true multithreading, the time taken for a for loop of half the range of the previous example should be half of the previous time taken, i.e. around 2.5 sec.

But this didn’t happen. This means that as both are around 99-100% CPU bound, both require GIL to execute. Hence, when 1 thread acquires the GIL, the other thread waits to receive the GIL back… hence the time required was roughly the same. Practically they never ran truly parallelly.

So, how do we run threads truly concurrently in Cpython? Many times we don’t even realize the bottleneck capacity of Cpython as majority of times we are not working with purely python code, for example working with numpy array, numba etc. we can get away with using multithreading/without acquiring GIL as once GIL is acquired, python calls a C program which runs in the background, and hence in that time the GIL can be given to other thread.

GIL HISTORY AND REMOVAL EFFORTS

GIL was first introduced in 1999, and had several positive and negative ramification-

-

Positives -

-

Simple

-

Easy to get right

-

No deadlocks as there is only 1 lock

-

Single threading is fast!

-

Good for i/o bound threads

-

-

Negatives -

- Bad for CPU bound tasks, as execution will always be on a single core. This was fine in 1992 as we would rarely see multi core CPUs back then. But the WORLD HAS CHANGED!

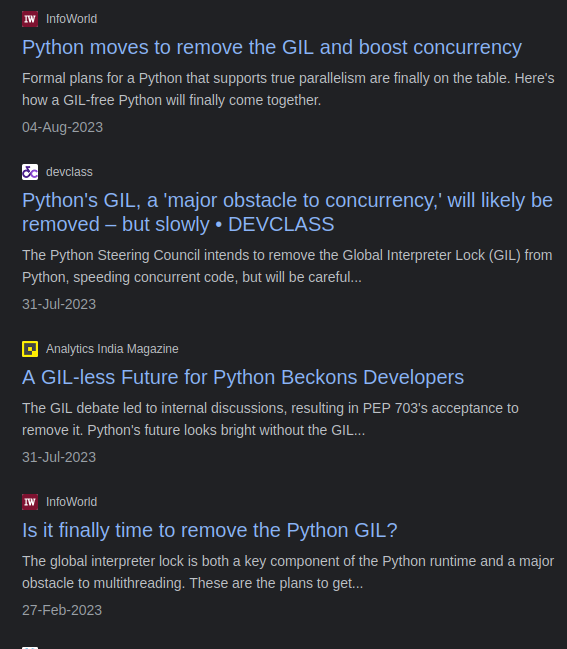

Unfortunately until and unless GIL is present this limitation would always be there, hence GIL removal has been a huge topic of discussion in the Cpython implementation.

In PEP - Python Enhancement Proposals - a proposal was made, to make the GIL optional, proposing to adding a build configuration and to let it run Python code without the global interpreter lock and with the necessary changes needed to make the interpreter thread-safe.

Over the years, various efforts have been made to overcome the limitations posed by the GIL:

-

Free-Threading (1996): An early attempt to address the GIL was called “free-threading,” but it didn’t fully remove the GIL and had its own set of complexities.

-

Gilectomy (2015): This initiative aimed to remove the GIL from CPython entirely. However, it turned out to be a challenging task due to the intricacies of Python’s memory management and extensive use of C libraries.

-

Recent Developments: “nogil” have been proposed, which explore ways to make Python more thread-friendly and possibly eliminate the GIL. These proposals aim to allow more parallelism in certain scenarios.

In the following sections, we would compare the performance improvements of these efforts done by other people and see how much improvements they actually give and at what costs.

There are three important aspects of Python to consider if we want fast, free-threading in CPython:

-

Single-threaded performance

-

Parallelism

-

Mutability (the ability to change the state or content of objects in a programming language, meaning that mutable objects can be modified after they are created)

The last of these, mutability, is key.

Almost all of the work done on speeding up dynamic languages stems from original work done on the self programming language, but with many refinements. Most of this work has been on Javascript, which is single-threaded and less mutable than Python, but PyPy has also made some significant contributions. PyPy has a GIL.

Self is an object-oriented programming language based on the concept of prototypes,

There is also work on Ruby. Ruby is even more mutable than Python, but also has a GIL. Work on Ruby mirrors that on Javascript.

The JVM supports free threading, but Java objects are almost immutable compared to Python objects, and the performance of Python, Javascript and Ruby implementations on the JVM has been disappointing, historically.

Performing the optimizations necessary to make Python fast in a free-threading environment will need some original research. That makes it more costly and a lot more risky.

There are three options available to the Steering Council (with regard to PEP 703:

-

Choose single-threading performance: We ultimately expect a 5x speedup over 3.10

-

Choose free-threading: NoGIL appears to scale well, but expect worse single threaded performance.

-

Choose both.

The pros and cons of the three options

Option 1:

-

Pros: We know how to do this. We have a plan. It will happen. Sub-interpreters allow some limited form of parallelism.

-

Cons: It keeps the GIL, preventing free-threading.

Option 2:

-

Pros: Free threading; much better performance for those who can use multiple threads effectively.

-

Cons: Some unknowns. Worse performance for most people, as single threaded performance will be worse. We don’t know how much worse.

Option 3:

-

Pros: Gives us the world class runtime that the world’s number one programming language should have.

-

Cons: More unknowns and a large cost.

FREE-THREADING Patch - link

Released in 1996, the Free Threading patch was built for Python 1.4 by Greg Stein. Unfortunately, Python 1.4 is very old and cannot be built on modern systems of today’s times. Hence, we would be looking into benchmarkings done by Dave Beazley in 2011.

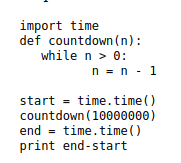

First, he wrote a simple spin-loop and see what happened:

Using the original version of Python-1.4 (with the GIL), this code ran in about 1.9 seconds. Using the patched GIL-less version, it ran in about 12.7 seconds. That’s about 6.7 times slower. Yow!

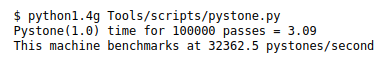

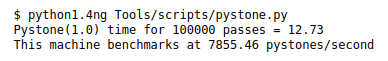

Just to further confirm his findings, he ran the included Tools/scripts/pystone.py benchmark (modified to run slightly longer in order to get more accurate timings).

First, with the GIL:

Now, without the GIL:

Here, the GIL-less Python is only about 4 times slower.

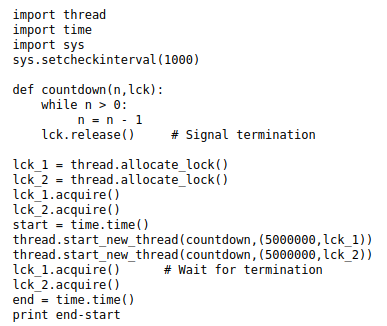

To test threads,he wrote a small sample that subdivided the work across two worker threads is an embarrassingly parallel manner (note: this code is a little wonky due to the fact that Python-1.4 doesn’t implement thread joining–meaning that we have to do it ourselves with the included binary-semaphore lock).

If we run this code with the GIL, the execution time is about 2.5 seconds or approximately 1.3 times slower than the single-threaded version (1.9 seconds). Using the GIL-less Python, the execution time is 18.5 seconds or approximately 1.45 times slower than the single-threaded version (12.7 seconds). Just to emphasize, the GIL-less Python running with two-threads is running more than 7 times slower than the version with a GIL.

Ah, but what about preemption you ask? If we return to the example above in the section about reentrancy, we will find that removing the GIL, does indeed, allow free threading and long-running calculations to be preempted. Success! Needless to say, there might be a few reasons why the patch quietly disappeared.

GILECTOMY by Larry Hastings - link

The earlier effort of removing GIL was more of a failure, as it worsened single thread performance as well as the multi threaded program ran slower compared running the same on single thread.

Hence, 3 political considerations Larry Hastings tried to keep in mind while building Gilectomy were -

-

Don’t hurt single threaded performance

-

Don’t break c extensions

-

Don’t make it too complicated

So, the things he did were -

-

Keep reference counting - It is a core functionality of Cpython and changing it would mean writing all the C APIs.

- Used atomic incr/decr which comes free with Intel Processor. But is 30% slower off the top

-

Global and static variables

- Shared singletons - all variables (in thread implementation) are public everytime

-

Atomicity - This is where the one big lock (GIL) would be replaced by smaller locks

- Hence, a new lock api was introduce

Here is a benchmarking code given by Larry Hastings himself, as the Gilectomy implementation has a lot of things like “str” etc. which don’t work as intended.

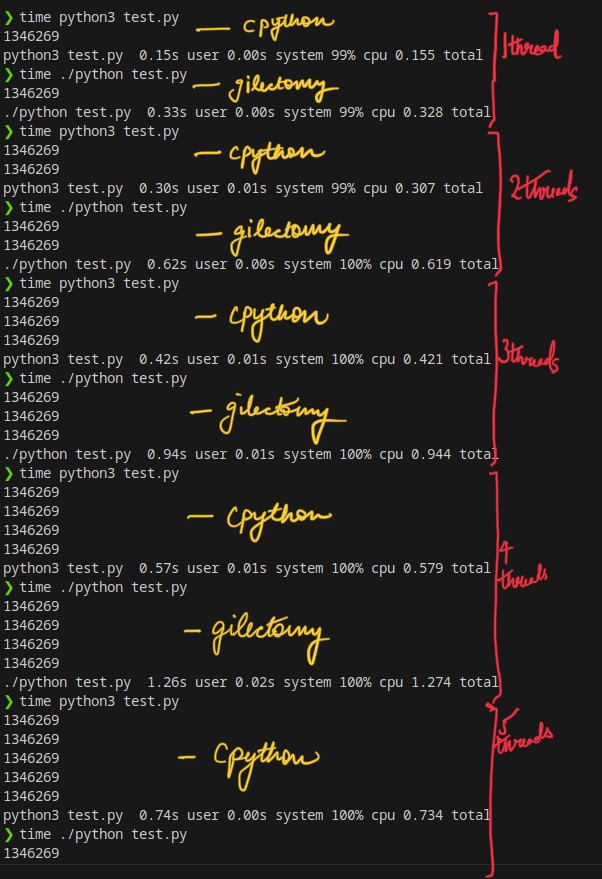

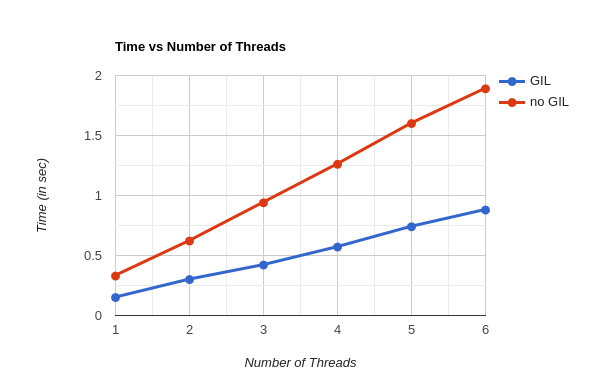

To benchmark, this code was run using both, Cpython (GIL) and Gilectomy (noGIL), on a 8 core, 2.80GHz system.

### Code 4.4.1: Benchmarking Code of Gilectomy -

### https://github.com/larryhastings/gilectomy/blob/gilectomy/x.py

import threading

import sys

def fib(n):

if n < 2: return 1

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

def test():

print(fib(30))

threads = 1 #changing number of threads here

if len(sys.argv) > 1:

threads = int(sys.argv[1])

for i in range(threads - 1):

threading.Thread(target=test).start()

if threads > 0:

test()

This code performs a CPU intensive task of calculating fibonacci of a large number (30 in this case) and running that CPU heavy task on multiple threads.

This code was ran on both Cpython-3.11 and Gilectomy-3.6.0a1

The reason for providing a benchmarking code by Larry was that many **features in Cpython did not work as it is in this Gilectomy’**s implementation of python. Something as simple as ‘str’ (string) had a very ambiguous behavior hence, he had to provide a code which could run on both Cpython and Gilectomy.

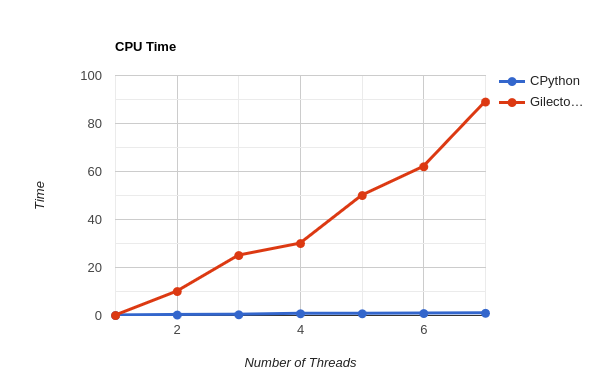

This graph represents the Wall Time difference in time taken by both the versions of Python. We can see the Gilectomy implementation is 2x times slower, which is not bad.

But here we can see that in terms of CPU time, Gilectomy is nearly 2x slower at 1 thread, but jumps to 10x slower at 2 threads and from there it keeps going up and up. At 17 cores, it is nearly 19-20 times slower.

In the context of this code, more CPU time is typically considered “bad” or inefficient. If you’re running multiple threads and each thread consumes a lot of CPU time, it can lead to high CPU utilization, potentially causing the system to become unresponsive for other tasks.

What happened to Gilectomy later?

The last update in Pycon 2019 was that after significant work Larry Hastings was still able to get the performance of his non-GIL version to match that of to Python with the GIL, but with a significant caveat; the default Python version ran only on a single core (as expected) - the non-GIL version needed to run on 7 cores to keep up. Larry Hastings later admitted that work has stalled, and he needs a new approach since the general idea of trying to maintain the general reference counting system, but protect the reference counts without a Global lock is not tenable.

nogil by Sam Gross - link

nogil is a proof-of-concept implementation of CPython that supports multithreading without the global interpreter lock (GIL). The purpose of this project was to show -

-

That it is feasible to remove the GIL from Python.

-

That the tradeoffs are manageable and the effort to remove the GIL is worthwhile.

-

That the main technical ideas of this project (reference counting, allocator changes, and thread-safety scheme) should serve as a basis of such an effort.

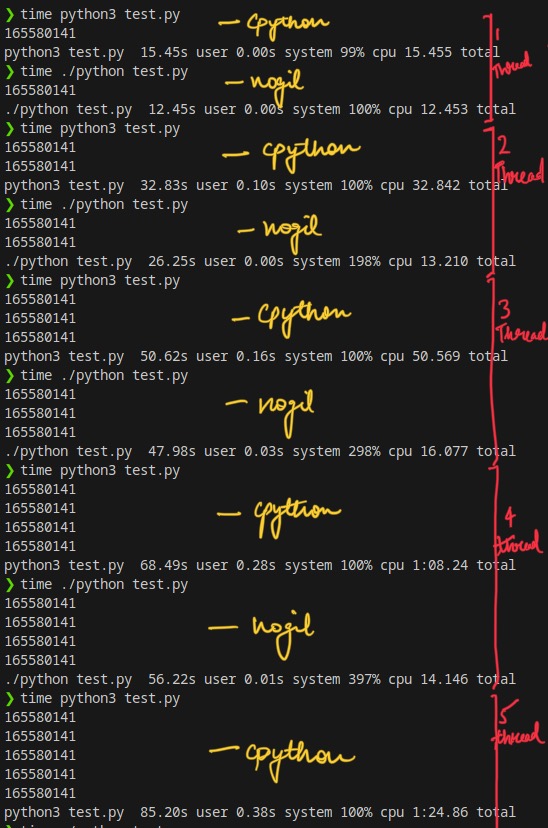

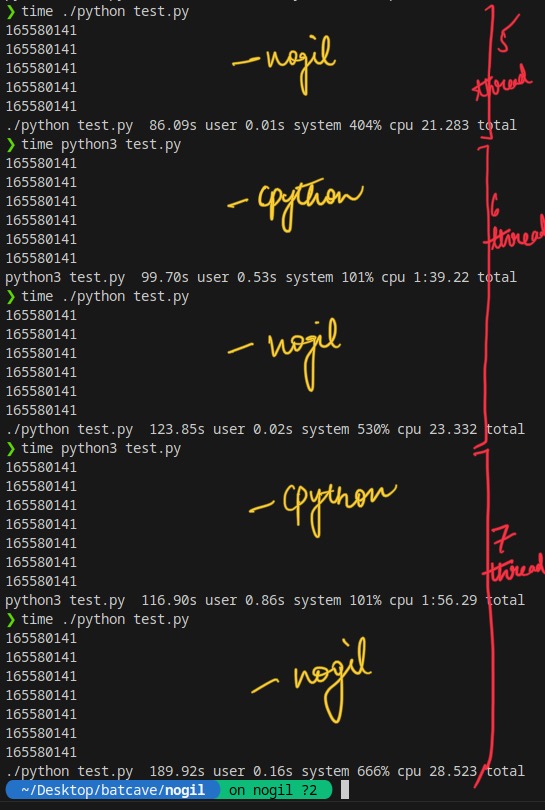

Let’s test on the same code, but calculating fib of 40 now -

### Code 4.5.1: Benchmarking code of CPU intensive task of calculating

### fibonacci of a large number, code ran on both Cpython-3.11

### and nogil-3.9.10-1

import threading

import sys

def fib(n):

if n < 2: return 1

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

def test():

print(fib(40)) # test function that calculates fibonacci number

threads = 7 # number of threads

if len(sys.argv) > 1:

threads = int(sys.argv[1])

for i in range(threads - 1):

threading.Thread(target=test).start()

if threads > 0:

test()

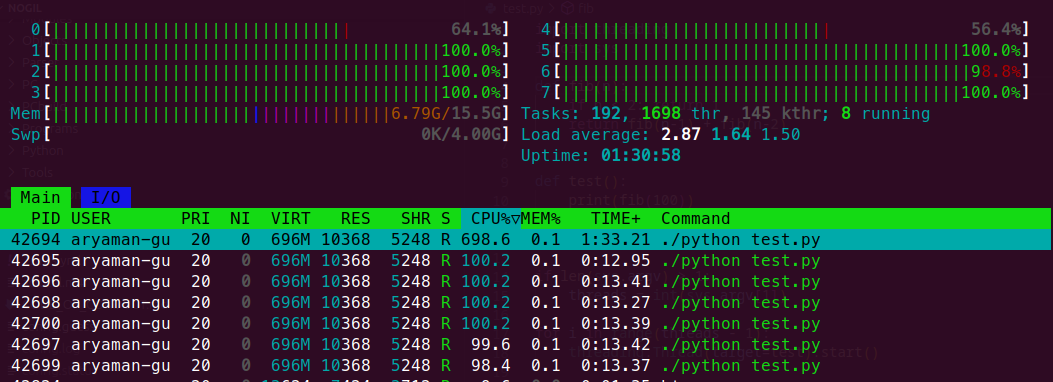

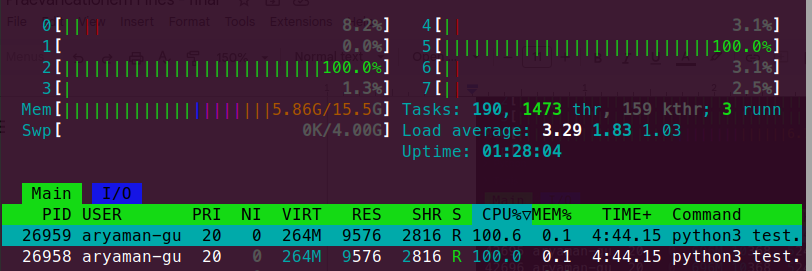

As we can see here, running code on nogil python implementation helped us to utilize more than 1 core at the same time without any restrictions, and all the 7 threads created are utilizing 100% of the respective CPUs.

In the same multithreaded process in a shared-memory multiprocessor environment, each thread in the process can run concurrently on a separate processor, resulting in parallel execution, which is true simultaneous execution.

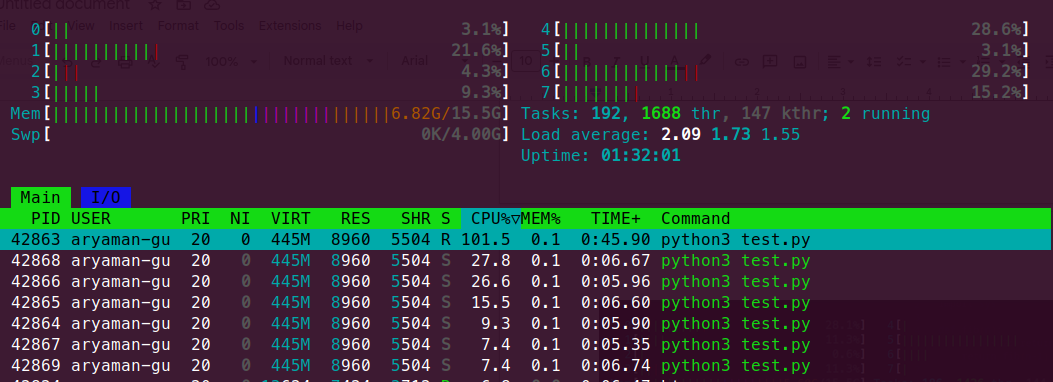

Meanwhile, creating 7 threads on Cpython implementation gives really poor performance, as even though 7 threads exist, only 1 of them is running truly at a particular moment.

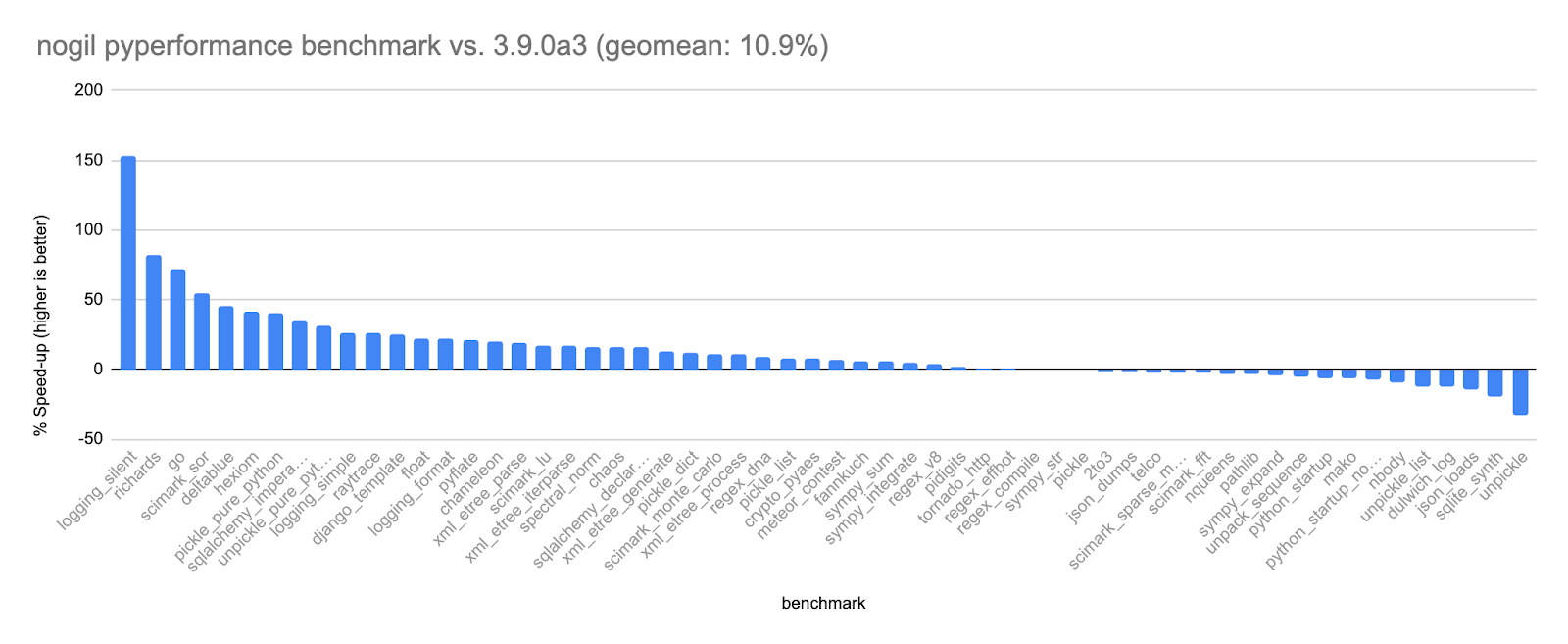

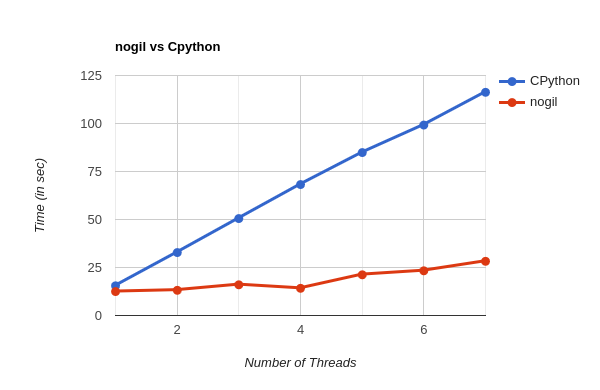

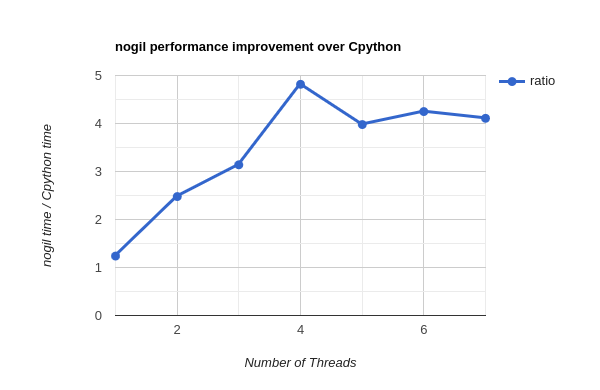

The shear performance improvement in nogil implementation over Cpython is mind blowing, making us wonder the highs MultiThreading in Python can touch -

As it is clearly visible, nogil completely outperforms the Cpython, even giving better performance in a single threaded program.

As clearly shown above, nogil can achieve upto 5x better performance in multithreaded programs, and gives slightly better performance in single thread as well.

Multiprocessing

The multiprocessing library allows Python programs to start and communicate with Python sub-processes. This allows for parallelism because each sub-process has its own Python interpreter (i.e there’s a GIL per-process).

Communication between processes is limited and generally more expensive than communication between threads.

Objects generally need to be serialized or copied to shared memory. Starting a sub-process is also more expensive than starting a thread, especially with the “spawn” implementation.

Starting a thread takes ~100 µs, while spawning a sub-process takes ~50 ms (50,000 µs) due to Python re-initialization.

### Code 5.1: Multiprocessing demonstration in python

import multiprocessing

def fib(n):

if n < 2: return 1

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

def test():

print(fib(50))

if __name__ == "__main__":

p1 = multiprocessing.Process(target=test) # creating processes

p2 = multiprocessing.Process(target=test)

p1.start() # starting processes

p2.start()

p1.join() # waiting for processes to finish

p2.join()

# both processes finished

print("Done!")

The multiprocessing library has a number of downsides.

-

The “fork” implementation is prone to deadlocks.

-

Multiple processes are harder to debug than multiple threads. Sharing data between processes can be a performance bottleneck. For example, in PyTorch, which uses multiprocessing to parallelize data loading, copying Tensors to inter-process shared-memory is sometimes the most expensive operation in the data loading pipeline.

-

Additionally, many libraries don’t work well with multiple processes: for example CUDA doesn’t support “fork” and has limited IPC support.

Conclusion

Seeing the level of improvement nogil is able to achieve, this is a big proof of a plausible world having a GIL-Free python which increases multithreaded performance by many folds, having no negative impact on single threading. Even though there is lot of work is still pending, there is no doubt that the PEP 703 will be accepted in the near future, but only time will tell.

References -

#breaking-boundaries #gil #no-gil #python #multithreading #aryaman-batcave